Author: Matthias Vögeler

matthias.voegeler@hshl.de

Date: June, 2020

Preliminary Remarks

The following findings have been filed to Solokeys in January 2020 and have been accepted.

Up to now, the issue that is located in an external library has not been solved. The associated repository is inactive for a couple of years.

However, the Solo that has been analyzed here, has an FIDO Authenticator Certification Level of 1, which means better than passwords. To my opinion, this statement is not affected by these findings.

Abstract

It is shown that the implementation of ECDSA, which is fundamental for FIDO2 and U2F, leaks some information of the most significant bits of the secret ephemeral key by performing a simple power analysis (SPA). This information can be used for lattice based attacks to recover the private key. In addition, the implementation of the scalar point multiplication algorithm is not functional correct.

Experimental Setup

A Solo USB-A for Hacker with firmware 3.0.0-3-g6b5d353 has been analyzed. The solo is operated by a Banana Pi Pro which sets an trigger signal on a GPIO Pin whenever a command is sent to the solo. The trigger signal as well as the USB current consumption is traced by a LeCroy HDO4000A oscilloscope.

An additional command has been added to the solo firmware in ctaphid.c to directly execute crypto_ecc256_compute_public_key in crpyto.c, which executes EccPoint_mult, that is also executed by uECC_sign_with_k, see uECC.c. So a scalar point multiplication is performed, the scalar is provided externally and the elliptic point is the basepoint.

Solokeys are using an external library for elliptic curve cryptography: micro-ecc. So the findings are potentially as well valid for other products that are using this library.

Code Inspection

Though the implementation of the scalar elliptic point multiplication algorithm for ECDSA is timing invariant, it does not use a randomized \(z\)-coordinate of the elliptic curve points, which make it vulnerable against SPA. Line 1258 of uECC.c executes

EccPoint_mult(p, curve->G, k2[!carry], 0, num_n_bits + 1, curve);

The 4th parameter is initial_Z which, if set to 0, sets the \(z\)-coordinate to 1 when line 874 executes XYcZ_initial_double. Since the ephemeral key is processed bitwise in the signature generation, two elliptic curve scalar point multiplications with the same sequence of leading bits lead to the same computations on the device, which generates similar power consumption traces.

Experimental Results

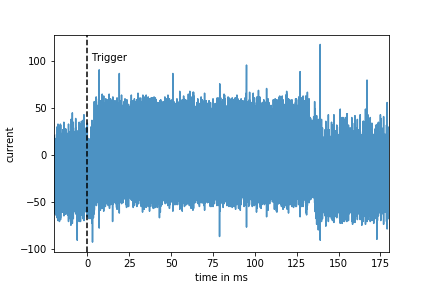

In total 256000 scalar point multiplications have been recorded, 1000 for each of the 8 most significant bits of the scalar (0-255). Figure 1 shows a power consumption trace of a complete scalar point multiplication. Obviously, the power consumption rises, if the device starts processing the input.

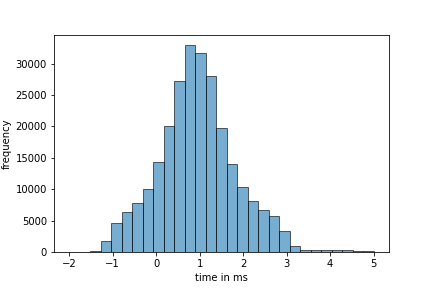

Since the trigger signal is not provided by the solo and the communication over USB is not time invariant the start of the processing of the command on the solo jitters relative to the trigger signal. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the offsets for the start of the command processing.

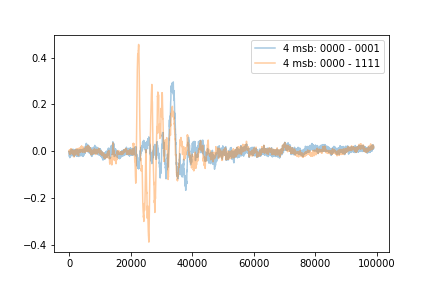

Although the data is very noisy, it was possible to properly align the traces. By comparing the differences in averaged traces for different sets of the \(n\) most significant bits, it was possible to identify the points in time where the \(n\) most significant bits are processed by the solo. Figure 3 shows the difference of averaged traces, where the traces with the 4 most significant bits equal to 0 are subtracted from those averaged traces where the 4 bits are equal to 1 and 15 respectively. With average traces the classification could be visually done.

In order to classify a trace according to the \(n\) most significant bits by using a single power trace, 80% of the traces have been labeled and have been used to train a machine learning algorithm and 20% of the unlabeled traces have been used to evaluate the classifier. It turned out that random forest classifier performed well.

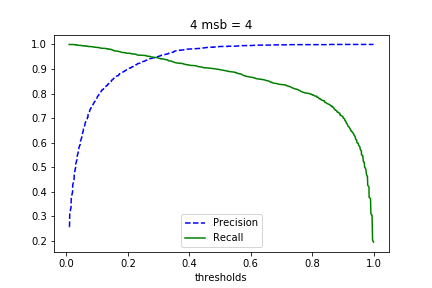

For a classifier there are two important performance measures. One is called precision, which is the ratio of true positives (tp) and the sum of true positives and false positives (fp). The other one is called recall, which is the ratio of true positives and the sum of true positives and false negatives (fn):

A binary classifier uses a threshold to assign the input to a class. Thus, varying the threshold enables a trade-off between the precision and recall, i.e. increasing precision reduces recall, and vice versa. Figure 4 plots the precision and recall against the thresholds of a binary classifier that decides if the 4 most significant bits are equal to 0100 or not.

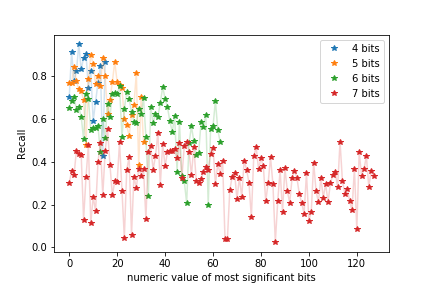

The threshold can be chosen, such that the precision is fixed to 95%. Figure 5 shows the recall of binary classifiers for the first 4, 5, 6, and 7 most significant bits, when the precision is set to 95%. It turned out, that the classification performance depends on the bit patterns and drops, if the number of the most significant bits to be classified increases. For a binary 8-bit classifier a precision of 95% could not achieved.

For example, the binary 4-bit classifier with a precision \(p=0.95\) has a recall of \(r=0.946\). A lattice based attack, where the 4 most significant bits of the ephemeral key are leaked, requires about 80 signature generations of a 256-bit key. The total number of signatures required in our scenario for a successful attack is then

For a 7-bit classifier with a precision of \(p=0.95\) and recall of \(r\approx0.4\) one can estimate

signature generations, where the lattice attack then requires a dimension of about 50.

Random forest classifiers can also be used as multiclass classifiers. Then each trace is labeled as one of \(2^{n}\) classes for a \(n\)-bit classifier. The results are shown in table 1. Precision and recall are the same.

| performance/bits | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| precision/recall | 90.6% | 89.4% | 83.0% | 70.1% | 42.2% |

Table 1: Performance of the Multiclass Classifiers

Countermeasures

A countermeasure has to prevent information leakage about the ephemeral key.

A simple countermeasure is to add randomization to the initial \(z\)-coordinate of the basepoint. If effective, it would even not cost that much performance.

Alternatively, an effective but more expensive countermeasure against information leakage of the ephemeral key is blinding \(k\) with a 32 bit random number \(r\):

Here, \(m\) is the order of the elliptic curve. This measurement would of course increase the running time of the scalar point multiplication by 12.5% for a 256-bit elliptic curve.

Another approach to mitigate information leakage is to randomly add dummy instructions to misalign the traces.

Conclusion

Obviously, the results show evidence that information about the most significant bits of a ephemeral key is leaking from a single power trace.

Although an attack seems unrealistic, because of the time required to collect all the signatures and the fact that FIDO2 and U2F requires user interaction, the implementation shall be considered as vulnerable. Attacks are always improving, they are not getting worse if time passes by. In particular, it might be possible to improve the measurement setup to reduce the noise in the data or to improve the post-processing of the data. Furthermore, machine learning algorithms allow a lot of tweaking with their parameters or a chaining of different classifiers will provide better results.

Additional Observations

The algorithm, that is implemented in uECC_compute_public_key, is a Montgomery ladder with \((X,Y)\)-only co-\(Z\) addition. It breaks when the point at infinity is reached. Since the ephemeral key \(k\) is regularized to achieve a constant timing, the algorithm breaks when the ephemeral key is 1, \(m-1\) or \(m-2\), where \(m\) is the order of the elliptic curve secp256r1. Thus, the implementation is functionally incorrect. On one hand, if the scalar is derived by a correctly operating true random number generator, the chance that \(k\)is either 1, \(m-1\) or \(m-2\) is negligible, it will simply not happen. On the other hand, if the scalar is received from outside by a third party an error state can be provoked, which might generate a security issue in the context of an application.

However, without the regularization as a countermeasure against timing attacks, the algorithm would treat a scalar of 1 as one of 3. That is because the implementation uses Algorithm 9 of this paper that is incorrect if the scalar is equal to 1.